When Your Expertise Becomes Your Constraint

The Decision That Your Frameworks Can't Integrate

You've assembled the best possible analysis. The financial team has modeled the transaction six different ways. Legal has outlined the regulatory exposure. Operations has projected implementation pathways. Technology has assessed the infrastructure requirements.

Every domain expert has delivered their conclusion. And the conclusions directly contradict each other.

This isn't a failure of expertise—it's a cognitive architecture problem that traditional consulting cannot address.

The Pattern Senior Leaders Recognize

The CFO's financial model says the investment pays back in 18 months with acceptable risk parameters. The General Counsel's legal framework identifies regulatory exposure that could invalidate the entire transaction structure. The CTO's technical assessment concludes that the implementation timeline makes the financial projections impossible. Operations confirms the timeline is achievable but only with organizational changes. Legal says create unacceptable liability.

Each analysis is correct within its own framework. Each expert has done exactly what they should. The problem isn't the quality of thinking—it's that these distinct knowledge systems don't have a natural integration point.

Most organizations respond by either:

Asking for "more analysis" (which produces more sophisticated contradictions)

Forcing premature consensus (which suppresses rather than resolves the conflicts)

Defaulting to whoever presents most confidently (which mistakes certainty for correctness)

None of these approaches address the actual cognitive challenge: How do you structure a decision when domain expertise produces competing realities rather than complementary insights?

What Metacognitive Architecture Reveals

The reason you can't resolve this through better analysis is that you're facing a cognitive complementarity problem disguised as an information problem.

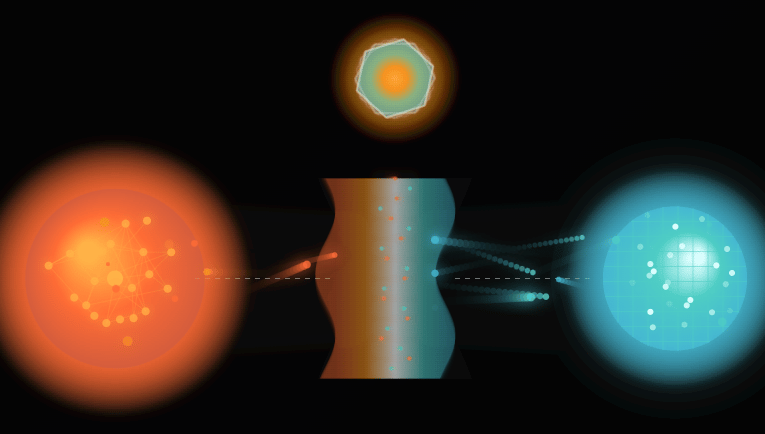

Your financial, legal, technical, and operational frameworks each reveal genuine aspects of the decision reality. But they're optimized for DIFFERENT time horizons, DIFFERENT risk tolerances, and DIFFERENT definitions of "success." They're not meant to integrate—they're meant to operate independently.

Traditional strategic decision-making assumes expert inputs are modular: gather the pieces, then assemble them into a coherent choice. But unprecedented complexity breaks this assumption. When the decision itself has no precedent, there's no template for how the pieces fit together.

This is where cognitive architecture becomes necessary.

The Integration That Can't Be Delegated

You cannot outsource this integration to any single domain expert because the integration point exists BETWEEN frameworks, not within them. The financial analyst cannot account for legal exposure they're not trained to evaluate. The lawyer cannot assess technical feasibility outside their expertise. Operations cannot override regulatory constraints.

And critically: AI analytical capacity doesn't solve this problem either.

You can feed all the analyses into the most sophisticated AI system available, and it will optimize within whichever framework you privilege—financial ROI, legal compliance, technical feasibility, operational efficiency. But it cannot tell you WHICH framework should be privileged because that choice exists at the metacognitive level.

The integration requires someone who can:

Recognize that competing expert conclusions represent different valid perspectives on the same reality

Identify which aspects of each framework are weight-bearing for this specific decision

Structure how human pattern recognition and AI analytical capacity complement rather than compete

Create decision architecture that makes the trade-offs explicit rather than hidden

This is not synthesis (finding the middle ground between positions). This is cognitive complementarity—architecting how distinct intelligences inform each other.

The Decision Architecture Question

When your organization faces this scenario, the question isn't "What should we decide?"

The question is: "What cognitive framework allows us to make this decision in a way we can defend not just in the outcome, but in the reasoning process itself?"

Because with unprecedented complexity, you often won't know if you made the right decision for years. What you CAN know is whether your decision architecture was sound—whether you integrated competing expert frameworks in a way that honored their distinct contributions without letting any single framework dominate inappropriately.

What This Reveals About Your Organization

If you're reading this and thinking "this is exactly the situation we keep encountering," that's diagnostic.

It means your organization has reached a level of strategic complexity where traditional decision processes—even highly sophisticated ones—are structurally inadequate. You don't need better experts. You don't need more advanced AI tools. You need a cognitive architecture that creates complementarity between the different intelligences you've already assembled.

Atosenography doesn't resolve these conflicts by picking the "right" framework. We design the metacognitive structures that allow you to make defensible decisions when multiple expert frameworks each reveal valid but incompatible aspects of reality.

This isn't about getting the decision "right" in an absolute sense—unprecedented complexity often means you won't know what "right" is until years later. It's about architecting the decision process so that however it unfolds, you can account for why you integrated competing expert judgments the way you did.

That's the difference between strategic decision-making and metacognitive architecture

*Conclusion: If your organization is facing decisions where domain expertise produces contradiction rather than clarity, the challenge isn't better analysis—it's cognitive architecture for how distinct intelligences inform unprecedented choices.